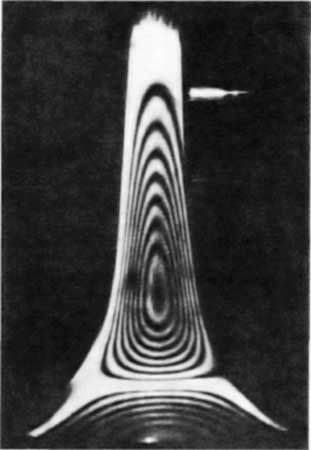

Fig. 1 Lateral vibrations of a trombone bell (Ando 1971)

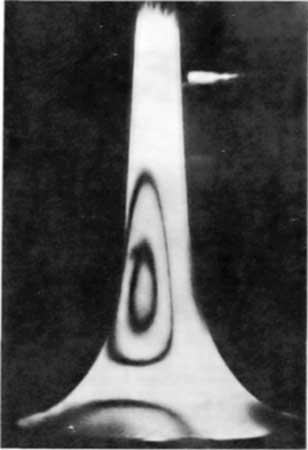

Fig. 2 Cross-sectional vibration pattern at 20 cm from the rim

Research

This paper reviews the research undertaken (some of it hitherto unpublished)

to ascertain the influence of materials on the musical properties of brass

instruments. Most work relates to the vibrational properties of trombone

bells (chosen for their large free vibrational surface) and in several cases,

the same set of experimental bells underwent a series of different tests.

There are several parameters which may be relevant to bell vibration studies,

and they include:

a) Wall thickness

b) Material (chemical composition)

c) Clamping positions (stays)

d) Rim size

e) Coatings (e.g. plate or lacquer)

f) Method of fabrication (one-piece/single seam/hand hammered)

It is reasonable to assume that if the material is thick, the effect of most

of the other parameters will be negligible. Hence recent work has tended to

concentrate on the effect of the variation in wall thickness. Presenting bells

of different thickness to players raises two other problems which are often

overlooked by experimenters:

1. Weight and Balance.

Players are surprisingly sensitive to

the weight and balance variation caused by a small change in bell thickness.

In the experiments performed by Smith {3}, each interchangeable bell of various

thickness had its own counterbalance to give identical weight and centre of

gravity. Under such conditions the players were unable to detect differences

due to weight or balance. Without this compensation the instruments were readily

identified.

2. Identical Bore Shapes. Blaikley {4}, referring to his experiments

with paper and metal bells {5}, states that "material has little influence

as compared with form." Backus {6}, for example, was also well aware of

the importance of using bells of identical bore profile when comparing materials.

However, other reports of experiments do not give the reader confidence that

the bores were identical. The experience of the author (and other designers)

suggests that bells (and other drawn and spun parts) of different wall thickness

do not retain the same internal dimensions when removed from the shape or mandrel.

Measurements on trumpet bells, for example, indicate a 0.15 mm increase in

diameter for thin bells (0.3 mm wall) when compared with thick items (0.6 mm

wall). This variation can have a significant effect on the musical performance

of the instrument, and is one explanation why manufact-urers often fail in

copying competitors instruments. Furthermore, materials of different constituents

will compound this error.

Vibrational Properties of Brass Bells

There is no doubt that a player can feel his instrument vibrating through his

hands in addition to the dynamic lip interaction, and so has good reason

to suppose that the material is adding to the musical quality of his instrument.

The vibrating walls can interact with the standing wave in the air column,

internally dissipate energy and radiate sound from their outer surfaces. If

resonant at particular frequencies (e.g. harmonic frequencies of the air column)

will the effect be constructive, detrimental or insignificant? The following

review of recent experiments hopes to answer this.

Ando {7} reports on how the

material affects tone quality through the results of Murakami and Kato. Fig.l

shows the various positions at which the vibration was measured along the length

of a trombone bell.

Fig. 1 Lateral vibrations of a trombone bell (Ando 1971)

Fig. 2 Cross-sectional vibration pattern at 20 cm from the rim

It appears that only one lateral measurement was made (along

the top surface) and it shows zero vibration at the bell rim, as though it

was clamped as a nodal point. Unlike the cross-sectional view measured at 20

cm from the rim (Fig.2); this does not correspond with the results of other

workers. He concludes that material has no important effect as far as harmonic

structure is concerned although a 1 dB s.p.l. was noted with a change to

a more rigid bell.

Smith {3} constructed a set of six similar brass trombone

bells using material of three different thicknesses. Each of the bells could

be fitted in turn onto a trombone body which was coupled to an artificial acoustic

driver. Time-averaged interferograms were produced for a large number of material

resonances, and further analysis showed a mathematical relationship between

the amplitude of the vibration of bells of different thickness {8}. The strongest

resonances were found at about 240 Hz with a considerably reduced amplitude

for the thicker bells (Fig.3). These results have been confirmed by other techniques

(Kitchen, Watkinson and Richardson) using the same set of bells.

Fig. 3 Holographic reconstruction of bell vibrations

with air column excitation at approximately 240Hz.

Left: 0.3mm wall thickness,

Right: 0.4mm wall thickness (Smith 1978)

A finite element method was used by Watkinson {2} to predict

the forms of vibration of the six bells. Although some of the input data is

roughly estimated, he confirms a strongly excited mode at around 250 Hz for

the medium bell and a weaker less consistent mode at a higher frequency (500

- 700 Hz). While Kitchen {9} agrees with the lower modes using a laser-doppler

velocimeter technique, he finds a stronger resonance in the 450 Hz region.

As expected, the modes of the thicker bells have higher frequencies than those

of the thinnest.

A further holographic test by Richardson {10} shows that the structural modes

by direct driving are very close in frequency to those measured by other techniques.

When acoustically excited the thin bells showed a (2, 1½) structural

mode close for the 4th harmonic of the air column. By changing the length of

the slide tube the structural resonance was more easily excited when the air

column mode coincides in frequency with this resonance, but there is no evidence

of strong coupling which would otherwise cause mode splitting.

Acoustical Properties of Brass Bells

Knowing the frequencies of the structural modes indicates a region in which

the acoustic spectrum might be influenced. The use of a human player source

for acoustic and vibrational measurements was found unsatisfactory due to

the poor repeatability of the results, hence the siren developed by Wogram

{11} was used by Smith {12} to produce the steady state spectra for the six

bells under investigation. The sound on the axis of the bell and at the players'

ear position (via an artificial head) were recorded and later analysed. Of

the three notes recorded (Bb1 58 Hz, Bb2 116 Hz and F4 349 Hz), only two

harmonics were significantly affected:

a) the 4th harmonic of Bb1 (i.e. at 232 Hz) and

b) the 2nd harmonic of Bb2 (i.e. at 232 Hz)

In both cases, the harmonic frequency is close to the structural resonance.

These two results and two others of harmonics not affected are shown in Fig.4.

a) 4th harmonic of Bb1 |

b) 2nd harmonic of Bb2 |

c) 5th harmonic of Bb1 |

d) 1st harmonic of Bb1 |

Subjective

Testing of Bells

The difference between ear and bell spectra amounts to about a 2 dB increase

at a particular harmonic for the thinnest bells. Having taken precautions

to equalise the weight and balance of the bells, ten of the best trombonists

were put through

a double blind test where the player is presented with a

prescribed random order of instruments. (all players play the same order)

{13} to ascertain whether they could distinguish between the six bells. The

statistical results showed that the difference between thin and thick bells

was so small that it could not be detected by any of the players. At a later

stage in the testing an electroformed pure copper bell (made on a similar -

but not the same mandrel) was added into the playing sequence. Under test conditions

this was not noticeably any different to the brass bells but when subsequently

played in non-blind tests it gained magical properties!

These results indicate that the bell thickness does have a significant affect

on the sound spectra measured at the players' ear position due to some sound

radiation from the material itself. However, under controlled conditions players

seem unable to distinguish between thick and thin materials.

References

{1} G. G. Fladmoe, Ed.D. Thesis, University of Illinois (1975).

{2} P. S. Watkinson, Ph.D.Thesis, University of Surrey (1981).

{3} R. A. Smith, Unpublished Report, Boosey & Havkes Ltd. (1977).

{4} D. J. Blaikley, Metronome, 35(1) 41-56 (1919).

{5} D. J. Blaikley, Workshop Notes (1874).

{6} J. Backus, The Acoustical Foundations of Music (London: Murray)(1970).

{7} Y. Ando, The Acoustics of Musical Instruments (in Japanese) (1971).

{8} R. A. Smith, J. Int. Trumpet Guild 3, 27-9 (1978).

{9} N. Kitchen, Final Year Undergraduate dissertation, I.S.V.R. (1980).

{10} B. E. Richardson, Unpublished Report, University College, Cardiff (1981).

{11} K. Wogram, Instrumentenbau 5, 414-418 (1976).

{12} R. A. Smith, Proceedings of the Institute of Acoustics (4E1)(1981).

{13} R. L. Pratt and J. M. Bowsher, JSV 57, 425-435 (1978).